“One is nostalgic not for the past the way it was, but for the past the way it could have been.”

This line from Svetlana Boym’s The Future of Nostalgia (2001) was what inspired Master’s student of Sociology, Richy Srirachanikorn [student member, Concordia] from the Technoculture, Arts and Games (TAG) Research Centre to question our use our digital tools to fulfill our aspirations. When we focus on past, we are often LOST in feelings, memories, and emotions. And this quest often leads to more losses: time away from others; e-waste from the promise of perpetually new devices; and a constant yearning for a past and a future that prevents us from living sustainably in the present.

When we relive our memories through our technological devices, we are chasing all that is “Lost.” So, when our digital culture is heavily fixated on the past and the future, we are constantly “Lost Again.” As such, Richy asks, what can we make of these experiences? Can digital nostalgia be extended towards a productive social outcome? Can it be more than just entertainment or respite?

Can media uncover past losses and prevent them in the future?

Honing on a form of generative nostalgia, Richy and his colleagues from the TAG Research Centre founded the Nostagain Network to bring together artists, game scholars, and media creators to ponder on this question. This led to the launching of their first symposium: LOST/AGAIN Digital/Nostalgia on February 4th, 2023 at the Milieux Institute.

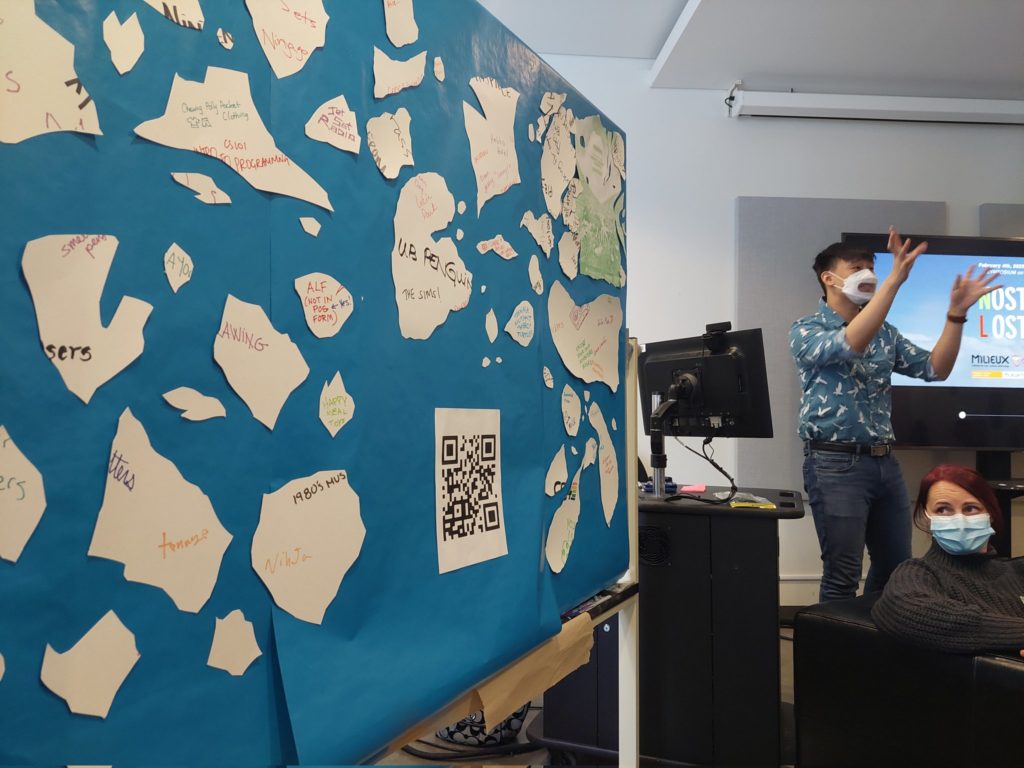

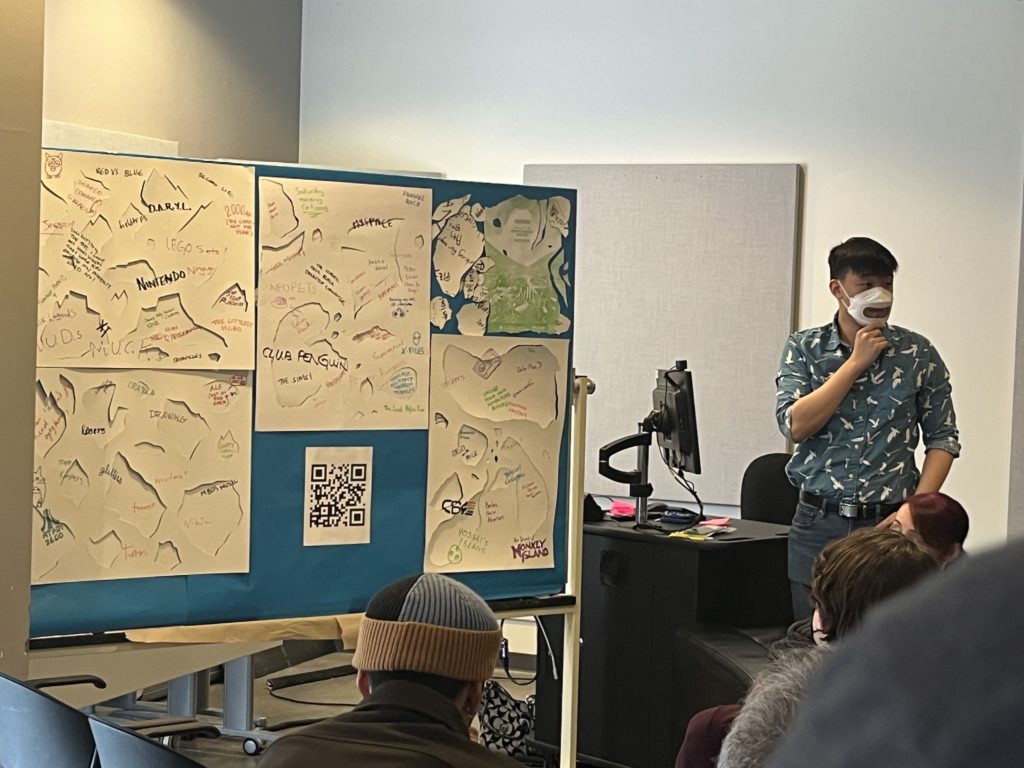

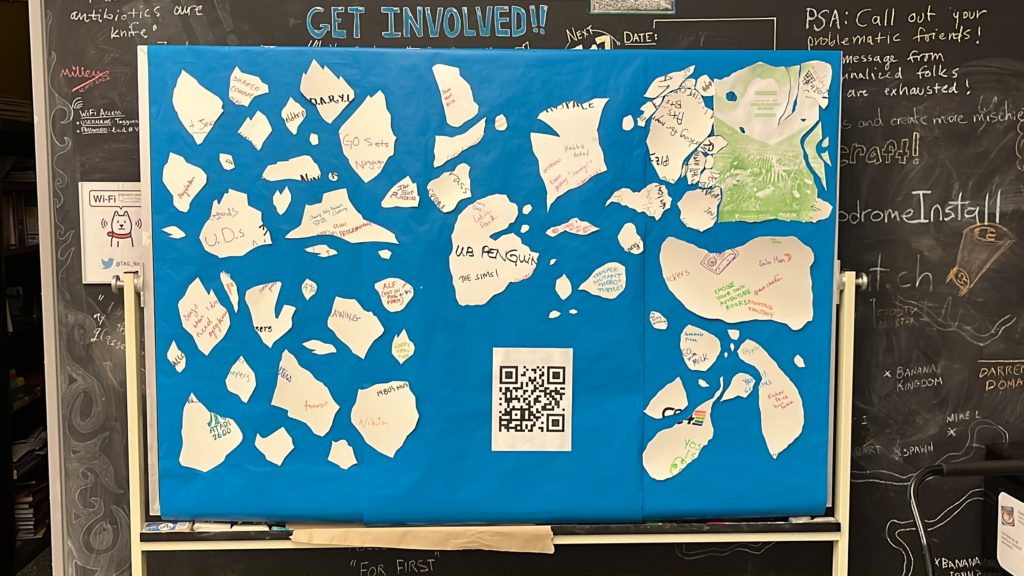

At the symposium, Richy presented a workshop titled Global Warning, which was a large moveable board with four large papers taped onto a blue backdrop. Throughout the day of other panel and workshop sessions, participants were encouraged to fill in their nostalgic reactions. At the end of the symposium, the board was filled to the brim with snippets of childhood cartoon titles, significant world events, people’s memories of pre-pandemic life, and obscure forms of media. Global Warning was able to demonstrate Richy’s argument that we are constantly “Lost Again” in our future and past. Simply put, we have become full-time nostalgics. Towards the end of the symposium, Richy invited four volunteers to tear down the sheets of paper on the wall, leaving behind pre-cut out shapes that were taped to the backdrop. What was left became a mural resembling the melting polar ice caps.

This research creation ties in with Svetlana Boym’s (2001) conception of chronophobia, the anxiety and paralysis emerging from the experience of transience, as we are “Lost,” living in the past or the future. Global Warning’s lasting image presents three key things about Richy’s research question.

First, nostalgia is not an individual experience, but a collaborative one.

It took the effort of everybody to fill the wall throughout the entire day in order to make it a “nostalgic wall”. Without collaboration, the wall remains a blank canvas. However, despite being loaded with nostalgic recollections, no single entry can capture what nostalgia truly means. A person’s childhood dog or the desire to go back home are all nostalgic things, but they are not experienced in the same way by everyone. As such, nostalgia requires the collaboration of participants to communicate what and why they are yearning for something.

Secondly, even after tearing down the wall, some words and phrases were luckily not cut off.

Yet, they too could not capture what nostalgia was. Things became blurry when sentences written by different people were read as one after the tear down. This resembles our memories and histories which are often lost, or blurred.

When we fixate on the past or the future, nostalgia’s temporality melts like the ice caps of the “vanishing present” (Boym 2001:351). Whilst nostalgia can bond people together, it can also oppose people, because no one can remember everything that has been lost. Therefore, Richy concludes that research creation activities such as the Global Warning wall can teach these lessons after prompting people be “Lost Again,” tearing apart the things which they’ve brought back onto the board. By highlighting the precarious but social nature of nostalgia, we have “found” the generative potential of things that aren’t digital (e.g., the blackboard wall) which revealed something about the relationship between technology and desires. In this sense, Global Warning was not just a wall of nostalgia, but also a nostalgic wall, reminding us to live responsibly, kindly, and mindfully, as we move into a future that the next generation will “find” in its present.